Food labels need to change in the fight against obesity

-

Date

Tue 13 Aug 19

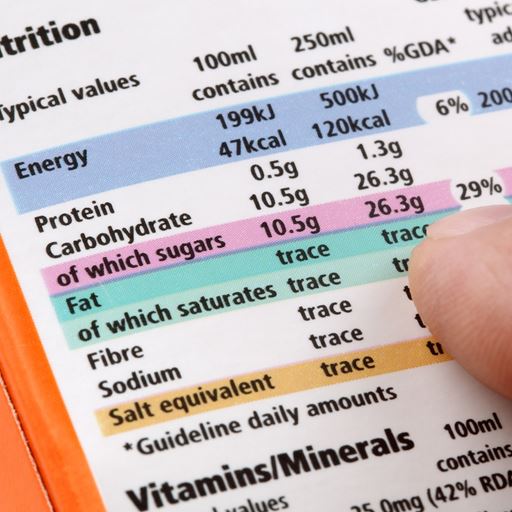

Researchers are calling for Government guidelines on food labelling to be amended after finding half of us misinterpret the information, so may not be eating as healthily as we thought.

In the first study to investigate people’s understanding of verbal descriptors such as ‘high fibre’ and ‘low fat’, which are meant to help consumers make healthy eating choices, researchers from the University of Essex found a huge discrepancy between the way information is interpreted and its intended meaning.

Typically people overestimate verbal descriptors like ‘high fibre’ and this could lead them to think they have had enough vitamins, minerals or fibre, when in fact their diet doesn’t meet dietary targets.

Dawn Liu, who led the study, explained: “The ability to judge the healthiness of food empowers people to fight obesity and diet-related disease. But our findings suggest there is a lot of confusion over food labels. Using terms such as ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘high’ may be simpler for consumers to understand, but these terms can also mislead them.

“One of the biggest problems is in the interpretation of information. For example, we found people believe a product described as being ‘high’ in fibre will provide them with between 48% and 68% of the amount they need each day. In fact, within Department of Health guidelines for manufacturers, a product described as being ‘high fibre’ could have just 30% fibre.

“This matters because over consumption of negative nutrients and under-consumption of positive ones impacts health and we know most people in the UK don’t eat enough fibre.”

Another problem identified in the study is the confusion caused when manufacturers use both verbal and numerical information on the same label – a breakfast cereal that is ‘high in fibre’, while providing 30% of your Guideline Daily Amount (GDA) of sugar, might seem to have a lot more fibre than sugar, when in fact both nutrients contribute equally to their respective GDAs.

Similarly it is difficult for consumers to choose between two products if the nutritional information is presented verbally on one and numerically on the other – is a ‘low-fat’ cereal better for you than one which provides 12% of GDA for fat?

“It would be beneficial if the Government’s guidelines for manufacturers were amended to be more in line with consumers expectations,” added Dawn.

The paper, People Overestimate Verbal Quantities of Nutrients on Nutrition Labels, will be published in the December issue of Food Quality and Preference. The full paper is available online.

It was written with fellow academics from the Department of Psychology, Dr Marie Juanchich, Dr Miroslav Sirota and Professor Sheina Orbell.