As part of a new series, Sanae Fujita, a Visiting Fellow of Essex Law School, has been recounting her work on educating her native country of Japan about human rights and exposing abuses in a country that rarely falls under the microscope.

Many people may think that Japan is a developed, democratic country with no particularly serious human rights problems.

In fact, I thought so myself when I came to Essex more than 20 years ago to study on the International Human Rights Law course.

I thought human rights were an issue for undemocratic countries with more serious social conditions, and not really relevant to Japan.

However, the language barrier and the positive image of Japan created by the foreign media have successfully concealed the reality that Japan has many serious human rights problems.

It was not until 2013, when I was a part-time staff member at Essex's Human Rights Centre, that I realised Japan was a country that needed more attention and help from the international community and could not be left alone.

This was triggered by the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets that the Japanese Government was drafting that year.

I then unintentionally started working on human rights issues in Japan, which I have continued to do for the past ten years.

At first, because of the positive image of Japan, even human rights activists asked me if there was a problem in Japan, and one foundation turned down my application for funding for my activities, saying that they had no plans to provide assistance to a rich democratic country like Japan.

Nevertheless, I continued my work through trial and error, with advice from my mentor in Essex and academic staff around me.

From Boiled broccoli to winning awards

At the start of my journey, I travelled frequently to Geneva, where the UN human rights organisations are located.

As is well known, prices in Geneva are extremely high. At first I had to pay my own expenses, and to save money, I remember getting food in the UK like boiled broccoli and bringing it over with me.

It seems a far cry from where I am now, a 2023 winner of the Information Distribution Promotion Award from the Hizumi Kazuo Foundation in Japan.

My Human Rights in Japan project

The Human Rights in Japan project consists of two directions.

One is to inform the international community, including the UN human rights bodies, about Japan's problems.

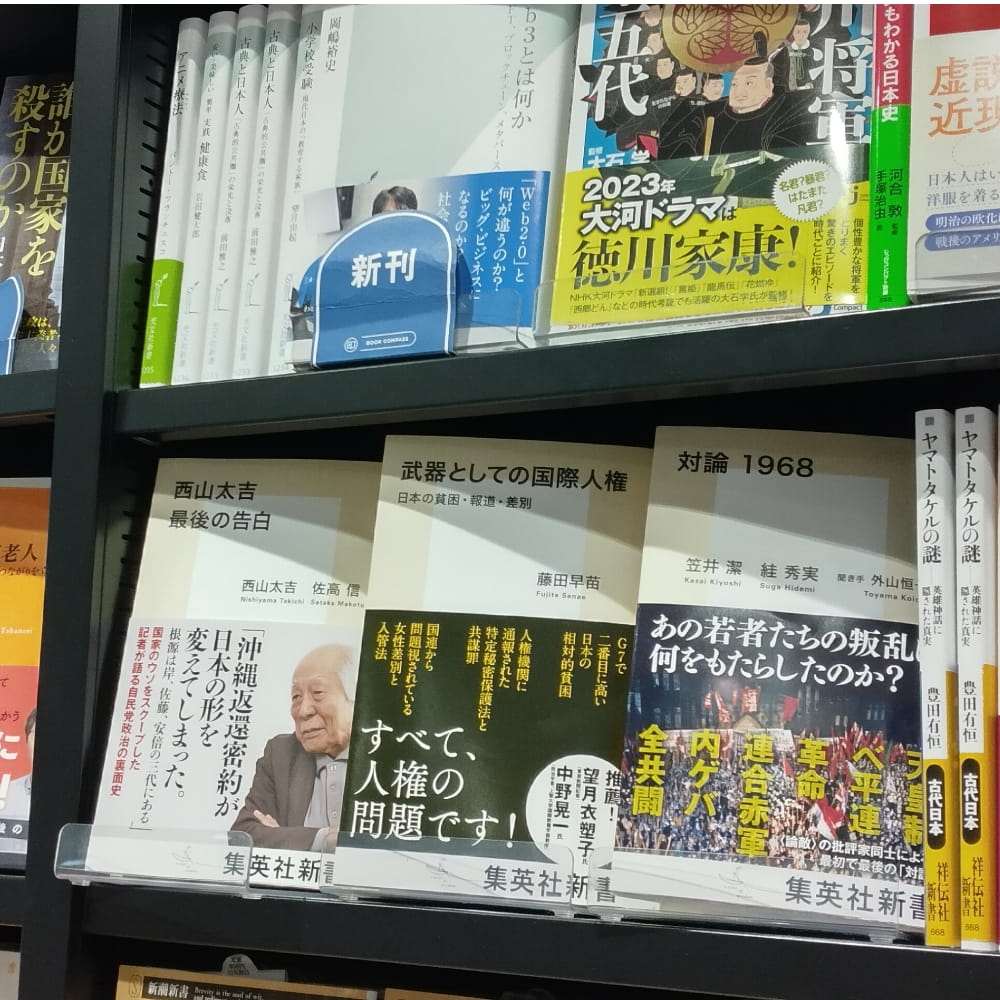

The other is to inform Japanese people about international human rights, as well as the more basic question of what are human rights through lectures, talks, media coverage and publications.

I have been working on this initiative for about 10 years now, financially supported by donations.

The trigger was the secrecy bill

I used to think that Japan was an 'okay country' until about 10 years ago.

So in 2013, I was astonished to learn that the Japanese Government had drafted the Bill on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets which deviates from international human rights standards, without any democratic process at all.

At the time I had few connections with people in civil society organisations in Japan, but I thought that the best I could do was to appeal to raise international awareness.

Then, with a friend who is an Essex graduate, I translated the bill into English and provided the information as a communication to the UN Special Rapporteur of Freedom of Expression.

Based on this information, they sent a UN letter to the Japanese Government containing strong concerns about the bill and recommendations for improvements, which were immediately reported by the Japanese media.

This was the first communication the Japanese Government had received from the UN Special Rapporteur.

The Japanese Government was then outraged and suspended the payment of the deposit to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights for a year as 'revenge'.

This was my first experience of using UN human rights agencies to tackle Japan's problems. Since then, I have provided information on a range of Japanese issues, including a conspiracy bill, safety of journalists, sexual assaults, immigration laws, the Fukushima nuclear disaster and trade unions. And timely recommendations for improvement have been issued to the Japanese Government on some of these issues.

On each occasion, the Japanese Government was furious.

Surveillance by the Japanese Government

There is no word or concept of 'critical friend' in Japanese.

The Japanese Government, which does not like to be criticised even if it is constructive, not only ignores the recommendations from the UN human rights experts, but also vehemently refutes them, repeatedly making statements that trivialise the authority and power of the UN human rights bodies and experts.

And it seems that they are also interested in 'finding the culprit' who provided the information.

I was also instrumental in making a country visit to Japan by the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression possible.

The Japanese Government had cancelled the visit request at the last minute once it had been accepted, but somehow the visit was realised in 2016.

However, it later transpired that the UN team and three individuals, including myself, who played key roles in supporting the investigation, were being monitored at all hours by the Japanese Government during the investigation period.

When I think back on it, I have an idea of what happened, and it sent chills down my spine.

As is well known, it is not unusual for human rights activists and defenders to be targeted by the authorities around the world, and Japan is no exception.