Principle O: An engagement challenge for care policy research

Using philosophy to understand the complexities of care

In this blog we address a very different dimension of public engagement. Professor Wayne Martin, Director of the Essex Autonomy Project, discusses how research engagement can be very different for those with disabilities.

‘Principle O’ is a clause within a landmark human rights treaty for persons with disabilities: those with disabilities should be actively involved in decision-making processes about policies and programmes. Below we begin to investigate how such a clause challenges us to satisfy the principles of ‘O’ in different research contexts.

The Essex Autonomy Project (EAP) is a high-impact research and public policy initiative, led by philosophers in the School of Philosophy and Art History, but involving extensive intramural and extramural collaboration. Its focus is the ideal of self-determination (“autonomy”) in care contexts (health care, eldercare, child care, social care, etc.), particularly in circumstances that involve intellectual, psycho-social and/or psychiatric disabilities.

At the Autonomy Project, we refer to that clause of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) Preamble as Principle O. Readers of this blog will recognise Principle O as a variant of the slogan that Danny Taggert recently discussed here: “Nothing about us without us.” Part of our challenge at the Autonomy Project is to figure out how to put Principle O to work in research that impacts upon care policy.

Rising to the challenge of satisfying Principle O

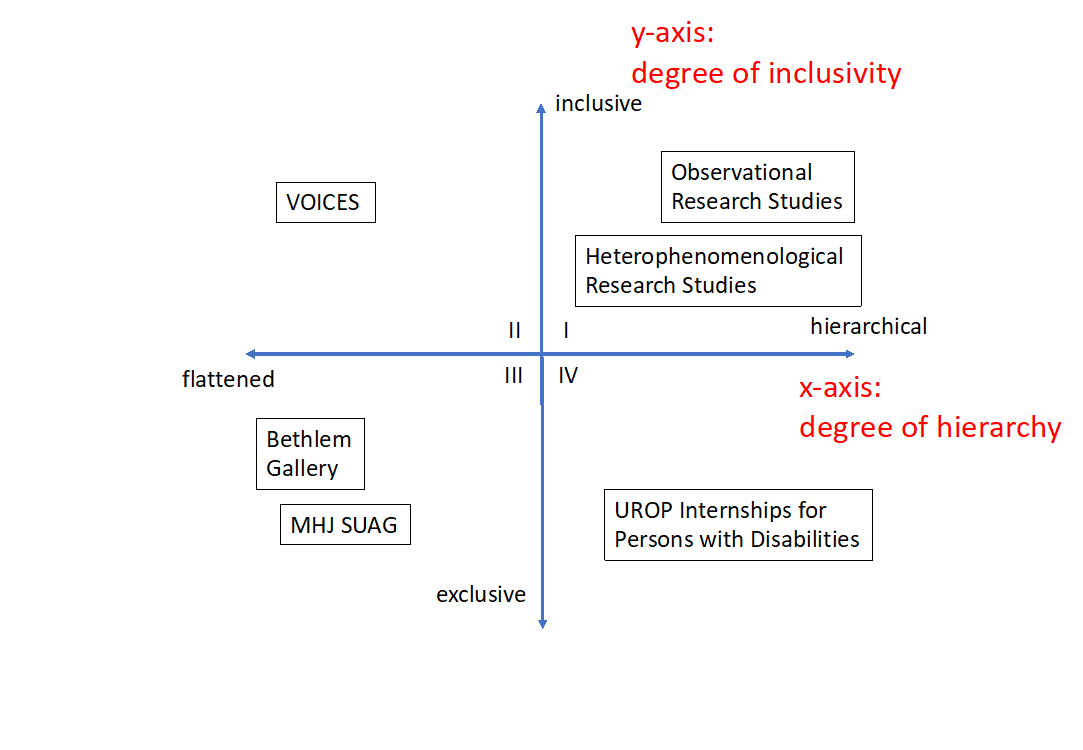

It is useful to distinguish two dimensions of difference in strategies for rising to the challenge of satisfying Principle O in research contexts. Different modes of research engagement can be more or less inclusive of persons with disabilities. That is to say: there can be a lower or a higher “bar-to-entry” for meaningful engagement. And, once a person with a disability is engaged, the form of that engagement can be more-or-less hierarchical: the person with a disability might occupy a subordinate position, or be an equal partner in (or a director of) the research or policy-making process.

With this distinction in mind, we can plot out strategies for satisfying Principle O in a four-quadrant state space (see Figure 1).

Experimenting with engagement strategies

Within the Essex Autonomy Project, we have been experimenting with engagement strategies that fall in at least three of the four quadrants in this state space. A number of our research interns under the University’s UROP Initiative, for example, have been persons living with psychiatric or psycho-social disabilities. These interns have made enormously valuable and substantial contributions to EAP research, but the bar to entry was high (only those with excellent academic credentials got an interview, and only some of them got the job) and the mode of involvement was hierarchical (they carried out research assignments designed by others). That’s Quadrant IV.

By contrast, for our current observational study at an NHS psychiatric hospital, the bar to entry is low (anyone capable of free and informed consent can be a participant) but the participation is even more hierarchical: participants are “engaged” by agreeing to have their ward rounds observed by members of our team. In our interview-based studies, there is less hierarchy (persons with disabilities are partners in long, open-ended conversations), and the bar-to-entry is higher (we need articulate research participants), but we are still in Quadrant I.

Inspiring artworks

But some of our most innovative engagement strategies lie in Quadrant III. On our Mental Health and Justice (MHJ) project, we work with a Service User Advisory Group (SUAG), and also with a group of artists associated with the Bethlem Gallery who have produced artworks inspired by their association with MHJ research teams. I think of these as Quadrant III forms of engagement. There is still a bar-to-entry: members of the SUAG must be able to review briefing papers and sit through long meetings; there are many persons with intellectual disabilities, including dementia, for whom this would be too much to ask. But once involved, these partners participate and contribute around a table where there is “flat” structure: no one is in charge except to manage the process – and that management role is taken by a pair of service users.

But what about that elusive Quadrant II: can public engagement in this research area be both inclusive and non-hierarchical? We are still on the hunt for engagement strategies that fall in this part of the state space, but we have seen some important innovations undertaken by other research groups. The VOICES project at the National University of Ireland (Galway), for example, paired persons with disabilities with academic partners who served as their “story tellers.” The pairs worked together for a period of months (or in some cases years) in order to tell the story of the person with a disability, with particular attention to the obstacles they faced in being recognised as full legal agents. The bar to entry in the VOICES project was low (even partners with very significant impairments were able to participate), and the relationship was entirely non-hierarchical. The data produced from that initiative has been invaluable to our own work on the Autonomy Project and has been methodologically ground-breaking as a strategy of engagement.

There is no single solution to the challenge presented by Principle O – no more than there is one research method that is suited to every research question. But in working towards full compliance with the UN Convention, innovation in engagement strategies is every bit as important, and challenging, as other forms of research and policy innovation.

Figure 1: Two Dimensions of Variation in Principle O Engagement Strategies